|

Excerpts from Ladies of the Court: Grace and Disgrace on the Women's Tennis Tour by Michael Mewshaw, 1993, Crown Publishers, NY This book is still in print in a revised paperback edition from 2001 with an additional chapter, obtainable from Amazon.com via the link above. The 1993 edition is reviewed here. Ladies of the Court is a description of the players, coaches, officials, and some tourneys on the 1991 WTA Tour. Ladies is similar in some ways to the description of the WTA Tour provided by John Wertheim's Venus Envy a decade later, while not so tightly focused on gossip about the players themselves. Although Mewshaw shows more general writing skill than Wertheim, some sports fans might have to keep a dictionary handy, in case they, like me, cannot quite recall exactly what words like "lugubrious" mean. The book is fairly informative about the WTA Tour in general, at a point when the WTA exec Gerry Smith was eager to break away from Virgina Slims/Philip Morris sponsorship, but didn't quite know how to do it. But the book dwells far too much on hyping sexual topics, particularly lady athletes relationships with their coaches, and whether it is appropriate that they have any. Unfortunately, when matches are described, it is usually in terms of losing, rather than winning, often belittling the skill of the players. Still, this book is probably an essential part of a record of the era of Steffi Graf, Martina Navratilova, Gabriela Sabatini, and Mary Joe Fernandez, as well as then 17-year-old Monica Seles and 15-year-old Jennifer Capriati. Mary Joe Fernandez, the subject the first 3 excerpts, was ranked in the top 20 in the WTA every year from 1989 through 1997, and had finished the year at # 4 in 1990. Mary Joe's career prize earnings totaled $5,258,471, 23rd highest all-time as of April, 2004. Broadcaster Mary Joe Fernandez interviewing Kim Clijsters at the WTA Championships in Los Angeles on Nov 2, 2002 |

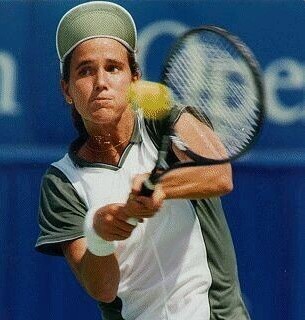

Mary Joe Fernandez at the Aussie Open (mid-90s)

|

|

At Rome's Foro Italico for the 1991 Italian Open (pages 46-48) ...when Seles and Fernandez emerged from the locker room, late-afternoon sun warmed the seats on the Tiber side of the stadium. Seats on the Monte Mario side were deep in cool shade. The moist clay was the color of smoked salmon. "What a beautiful Caribbean maiden," a German journalist said of Fernandez. Although an American, raised in Miami, Mary Joe (a translation from Maria-Josť) had been born in the Dominican Republic of a Spanish father and a Cuban mother. A mahogany-brown, imperially slim girl of nineteen, she had a cat's sinuous grace and slinky deceptive speed. Dark hair hung down her back in a single braid. Her sinewy legs were those of a dancer, her frail upper body that of a model. She was the fifth best woman player in the world, yet utterly unknown to the mass public. To redress the problem of her anonymity, she had recently left IMG and was now represented by Ion Tiriac... At two games apiece in the first set, Mary Joe squandered a couple of break points, and as so often happens when a player lets a chance slide, she found herself in trouble in the next game. She lost her serve to 2-4, then watched as Seles held to 5-2 with an ace. When Monica served for the set at 5-3, Mary Joe walloped a few inside-out forehands that caught her by surprise. After breaking to 4-5, Fernandez scrabbled to 5-5, but the running and retrieving had exacted a toll. Her thin shoulders sagged, her chest heaved. She took her time between points, trying to catch her breath. But Seles kept boring in and closed it out 7-5. The set was a microcosm of Fernandez's career--stylish, close, and finally futile... Still, she showed little weakness in the second set, and when she won 6-2, it looked as though she had turned the momentum in her favor. In the third set, Monica leaped out to a 2-0 lead, only to have her serve desert her. As the temperature plummeted and spectators turtled down into their sweaters, Mary Joe broke Seles three times straight. The trouble was she couldn't hold her own serve. At two sets and four games apiece, the clock on Campo Centrale indicated that the girls had been going at it for two hours, and the question was which one had the guts to raise the level of her game. Fernandez tried to take the initiative and the net, but Seles held to 5-4. Serving to stay in the match, Mary Joe steered a tired forehand into the net and slipped to 0-15. At 0-30 she chipped the ball, charged, and got passed to 0-40. Fernandez saved two match points, but pushed an approach shot long and listened to the umpire intone another sad benediction on her ambitions. "Game, set, and match, Miss Seles." |

|

At Roland Garros for the 1991 French Open, talking to Mary Joe Fernandez's coach (pages 90-94) Ernesto Ruiz Bry, Mary Joe's coach, loitered in the player's lounge, which, this late in the tournament, had no players in it. A tan, handsome Chilean with a shock of black hair and high cheekbones, Ernesto had played briefly on the men's tour before he started coaching. Guillermo Vilas had been his most famous pupil... In early April 1991, Ion Tiriac [then Mary Joe's agent] had asked Ernesto to train Mary Joe. After two months on the job, Ernesto thought they were making progress. While Fernandez hadn't won a title, she hadn't lost any ground either. Her defeats here and in Rome had been to talented girls--Seles and Sanchez Vicario--and it took time to change a player's mentality so that she could then change her game. Against top competition, she had to realize that she couldn't wait for her opponents to make mistakes. She had to beat them. There was, Ernesto emphasized, a big difference. There was, also, a difference between coaching men and women. "With a woman," he said, "you have much more work to do on the technical side. Normally a top-thirty player on the men's tour is technically complete. Not the women. I can have more satisfaction working with a woman because I can teach her more both technically and in terms of strategy." But what they lacked in technique, the women compensated for with superior concentration. "Mary Joe listens," Ernesto said. "She learns very fast. She's on time and she's disciplined. They are more into tennis, the girls. The men have other interests. I used to have to drag Vilas away from his music to get him to practice. Agenor, too, is a singer and has made an album. And, of course, the boys are thinking about going out, thinking about girls. The go to a disco and get to bed at three in the morning. But Mary Joe, I don't remember her going to bed after midnight. She never goes to discos. Her parents are very strict, and she's obedient. She's intelligent, but she's a simple person with simple tastes. She's beautiful, but she dresses simply, not in designer clothes. The only difference between her and the girls she went to high school with is she drives a Porsche--not even the best Porsche," Ernesto added in amazement. Mary Joe's simplicity and niceness were not, however, what prevented her from breaking through, Ernesto insisted. "She's very competitive. And being nice you can be a champion. Gabriela's nice. Steffi's nice. Mary Joe is very intelligent," he repeated, then mentioned again, as everyone did, that she had finished school. In his opinion, girls who had no education were headed for trouble. "No culture," he said, "and you lead an incomplete life." As for himself, he was "very involved with art. I paint. I have had exhibitions. At one time I stopped coaching for a year and a half and just painted. When I'm alone in the hotel room, I'm painting. But I know for a player the tour gets boring. When I see Mary Joe closing herself in her room, I know she's lonely. A guy can go out, can go look for girls, look for sex. But a girl looks for love and you don't find that in two days at a tournament..." Although he had spoken of Mary Joe's loneliness, her father traveled with her, and Ernesto thought this was a good idea. "Other girls travel alone and they're never relaxed. I see them at breakfast and the frighten me, they're so tense. I've been doing this a short time, but from what I see I don't think it's good for a girl to be on the tour alone. "The low-ranked players, I don't know how they can even afford to pay coaches," Ernesto said. "Some of them I think are just with boyfriends. She teaches him to play, then makes him her coach. It's a way to justify things. When a girl doesn't have enough money, she hires a good friend instead of a good coach. And he can even help her arrange practice courts and airplane reservations. At that level, perhaps it's more important to have a boyfriend. Later on, when she has more money, she can afford a boyfriend and a coach." He viewed the fact that girls in their teens got sexually involved with middle-age coaches as unsurprising, perhaps inevitable. "Sometimes with an older man, a girl gets more stability. We see this not just in tennis, but elsewhere in life." Ion Tiriac, looking rumpled and grumpy as a bear wakened prematurely from hibernation, strolled over to where Ernesto and I sat. His trademark mustache, woolly as a caterpillar, had turned white at the tips, and he had taken to wearing the sort of tinted prescription glasses you used to see on Eastern Bloc strongmen. Otherwise, the advancing years had left Tiriac unbowed. With no time wasted on pleasantries, he broke into the conversation and told Ernesto that they had to talk. Ernesto asked me to come back in fifteen minutes. When I did so, he was alone and looked as he had before--like just another tan, healthy fellow in jeans and a faded chambray shirt kicking back in the player's lounge. But his tone had changed; he spoke with an edgy directness. He said it was hard to understand Mary Joe's defensive mentality, and thus hard to convert her into an offensive player. "I hit with her, but I can't get close to her off the court. That's when you get to know somebody. That's when you learn about their confidence and their psychology. But Mary Joe, whether she's happy or sad, how her mind is before a match, I don't know because she's always with her family whenever we're not practicing. To see matches together, to talk tactics, that's what we need." He crossed his legs and folded his hands on his knees. He appeared to be locking up, trying to keep his answers short. Yet he blurted, "A lot of parents want to coach their daughters. This tennis tour, it's not the real world." "How's that?" "In the real world nobody lives all year in five-star hotels and travels by limo. But on the circuit even journalists and parents and low-ranked players live like movie stars." After a pause, he said, "These girls, they don't really have any experience. They are very naive. They think they know a lot. But since twelve years old they're hitting a ball. The circuit takes a lot out of them. As he fell silent again, I thanked him for his time and said I'd see him at Wimbledon. Ernesto said he wasn't going to Wimbledon; he wasn't coaching Mary Joe any longer. The words came tumbling out of him with amazingly little emotion. Tiriac had just told him he was finished. He had expected to stay with Mary Joe through grass-court season. He had thought they were making progress. "The only problem was Mary Joe's father. He was always there at practice, always making a remark. I tried not to answer back, but not to answer a sixty-five-year-old man can be impolite, too. I was afraid it could be ugly." Occasionally he had handed the racquet to Mr. Fernandez, as if to tell him, Okay, you do it. Instead, Mr. Fernandez had hired Juan Avendano, a former player on the men's tour, a baseliner who had rarely come to the net in his career. Ernesto complained that he could have helped Mary Joe. He could hit with topspin or slice, he could impersonate any player's style. The trouble was he never had a chance to develop a close rapport with her. In his opinion, some of the most important coaching occurred off court while talking to a player, watching matches and discussing tactics, learning about a woman as a person so he could help her more as a player. "Maybe that's what Mr. Fernandez didn't want," I said. "For you to develop a close personal relationship with his daughter." Ernesto mulled this over for a moment. "Yes, a lot of players and coaches wind up in bed. But that idea, that thought that people have, makes me mad. Already an umpire told me when I first started coaching Mary Joe, 'You'll end up in bed with her.' I wanted to hit him in the face. Maybe that's what Mary Joe's father was afraid of. I don't know." And now Ernesto Ruiz Bry was tired of talking about it. Tomorrow he would fly to Monte Carlo and try to arrange an exhibition of his paintings. |

|

At Wimbledon for the 1991 Championships, talking to Mary Joe Fernandez (pages 128-130) Once we were alone, I asked, "Who are you hitting with here?" Mary Joe said Tim Gullikson, Tom's twin brother, was around. He was on the USTA coaching staff, and sometimes she worked with him. But she now traveled with Juan Avendano. "He knows I want to come to the net, and even though he never came to the net, he knows that's how you win." "What happened to Ernesto Ruiz Bry?" "He was painting," she said. "He had a big exhibition coming up. He wanted to take a break. He was asking permission to take off other weeks for his painting and exhibitions." "That's not what Ernesto told me. He said your father didn't like him and decided to get rid of him." Mary Joe crossed her long brown legs and wagged her foot back and forth. Her pretty face was as smooth as a pond into which one small pebble had been dropped. There was just the slightest ripple of a reaction. "No. Dad was disappointed Ernesto wanted to take time off. I had a lot of fun on court with Ernesto. It was a little difficult, though, because he hit with a lot of spin and I'd rather hit with someone who hits flat. I couldn't get grooved on his strokes." This not only contradicted Ernesto's version of events, it conflicted with what a few Hispanic players had told me. They too had asked what happened to Ernesto, and Mr. Fernandez explained that when he didn't agree with certain drills and had suggested different ones, Ernesto responded by holding out the racquet and saying, "You coach her, you show her, if you know how." Offended by what he saw as indolence, Mr. Fernandez had dropped Ernesto. But Mary Joe wouldn't budge. Ernesto had quit because of his art, she insisted. Still, she didn't deny that her father played a major role in her life. She was close to him, to her whole family. "My foundation has been very good. That's why I stayed in school. I'm different from other girls not because of my education, but because of my family. You see other girls on the tour, I wish they talked more or knew more. They dropped out of school at an early age and all they did was bang tennis balls. This is a short part of your life. What are they going to do later? I don't want to judge people, but it's sad." ...The conversation swung back to coaches, and Mary Joe Fernandez remarked, "It's very important, the relationship between a coach and a player. You have to have a lot of faith in a coach. But you click with some people and not others." I repeated Ernesto's assessment of the problem. Since he couldn't get to know her off court, he couldn't teach her as well as he wanted to. "Yes, that might have helped," she blandly replied and let it go at that. |

|

At Wimbledon for the 1991 Championships (pages 122-123) Years ago the Competitor's Lounge at Wimbledon had, in theory, been the sacrosanct preserve of players and their guests. But, in practice, it had always been a throbbing hive of hustlers, racquet dealers, clothing reps, agents, tournament directors, assorted groupies, gofers, and camp followers. Now journalists had access to this sanctuary. Flashing a special forty-five minute permit, I passed the guard at the door and, during yet another rain delay, climbed the stairs to the third floor and stopped at the Prize Money Office, where a woman cheerfully explained her job. Once a player lost, he or she popped in here to pick up a check. A player's agent or manager could collect prize money, but only with written permission. "Even though we know, for example, that Ion Tiriac is Boris Becker's manager, we have to have it in writing before we'll hand over Becker's money," the woman said. "What if the players want cash?" I asked. "Then they carry the check to the bank here on the grounds." "Do you deduct U.K. taxes?" Indeed she did. Foreigners paid a flat 25% on their winnings, but they received a £150 per diem exclusion before British taxes bit into their purse. The Prize Money Office also deducted WTA dues and fines for code violations. Although it sounded complicated, she assured me that "because of computers, we can get a player in and out in thirty or forty seconds. That's a lot different from the old days." She smiled sweetly. "Now I'm afraid I can't say anything else." "Do you ever get any strange requests?" The smile never faltered. "Lots, but I'm not allowed to tell you." |

Mary Joe Fernandez Career Record from the ITF Database, (does not include all events)

Mary Joe Fernandez profile at WTATour.com

Find tennis shoes made by: adidas -- Nike -- Fila -- Reebok

Find tennis racquets made by: Yonex -- Wilson -- Head -- Prince -- Babolat

Find tennis balls made by: Wilson -- Dunlop -- Penn -- Tretorn -- Slazenger

Tennis pages at quickfound.net:

- Tennis History Book Excerpts:

Ladies of the Court by Michael Mewshaw

Tennis Styles and Stylists by Paul Metzler

Chrissie: My Own Story by Chris Evert with Neil Amdur

Courting Triumph by Virginia Wade with Mary Lou Mellace

The Game by Jack Kramer about Pauline Betz & Gussy Moran & more

Beyond Center Court: My Story by Tracy Austin with Christine Brennan

Courting Danger by Alice Marble with Dale Leatherman

Evonne!: On the Move by Evonne Goolagong with Bud Collins

Court On Court: A Life in Tennis by Margaret Smith Court

Goddess & the American Girl: Suzanne Lenglen & Helen Wills by Larry Englemann

Hard Courts by John Feinstein about Mary Carillo & John McEnroe & more

A Long Way, Baby by Grace Lichtenstein about Rosie Casals

Monica by Monica Seles & My Aces, My Faults by Nick Bollettieri Seles at Bradenton

Tough Draw by Eliot Berry about Nick Bollettieri

The Courts of Babylon by Peter Bodo: Tournament Draws

The Courts of Babylon by Peter Bodo: Dawn of the Pro Tours

- Tennis Articles

1946 TIME: Pauline Betz, Doris Hart, Beverly Baker, Gussie Moran

plus current tennis article feed

1951 & 1952 TIME: Maureen Connolly - Tennis News and Links

- WTA 2004 Desktop Wallpaper

- Justine Henin-Hardenne Desktop Wallpaper

- Maria Sharapova Desktop Wallpaper

- Anastasia Myskina Desktop Wallpaper

- Anna Kournikova News and Links

- Anna Kournikova Desktop Wallpaper

- Martina Hingis News and Links

- 2004 WTA Player Interview Videos

This page's URL is: //tennis.quickfound.net/history/ladies_of_the_court.html