Teach Tennant & Alice Marble |

Excerpts from Courting Danger: My Adventures in World-Class Tennis, Golden Age Hollywood, and High-Stakes Spying by Alice Marble with Dale Leatherman, 1991, St. Martin's Out of print, but still readily obtainable used from Amazon.com via the link above. Courting Danger is very entertaining reading. In fact, much of the book reads like a pretty good fiction novel, which combined with some of the amazing events described can give the reader the feeling that it might not be entirely true. But there is no reason to doubt Alice Marble's word; the book is probably written this way as a result of her photographic memory. The only other complaint that might be made about the book is that it doesn't go into enough detail in describing some important matches. Courting Danger is clearly written, and includes an index, which is useful for historical research and reference purposes. It also has a section of great photos well-printed on glossy paper, 3 of which are shown on this page. |

|

Early years (pages 1-5) [My father] Harry Marble was proud... I was only seven when he died, too young to understand the irony of his being injured in a car accident and later dying of pneumonia, when he'd topped two-hundred-foot trees every day and had never gotten hurt... I was old enough to know our lives had changed, and to feel the pinch of being poor. It was 1920. We had recently moved from the Sierra town of Beckwith to San Francisco, and my mother Jessie was left with five children: Dan, thirteen; George, eleven; Hazel, ten; Tim, four; and me. Dan and George soon quit school to work six days a week laying hardwood floors. I was glad I was too young to quit school and work. Once I learned to read, I discovered that I remembered everything I read, almost word for word... I was gifted with a photographic memory, the teacher said, and very, very lucky... At thirteen, baseball became the center of my universe. Every summer day, I was at Recreation Park, watching the [minor league San Francisco] Seals play. Joe DiMaggio, Lefty Gomez, Lefty O'Doul, Frank Corsetti and Smead Jolly all played for the Seals; most of them went to the Yankees later. Admission cost a dime... My ten-year-old brother Tim and I went early with our gloves and a ball so we could play catch in the bleachers before the game... We were doing just that one day when a player walked over to the fence. "Say, boy," he called, "how'd you like to climb down and play with me?" ...Before he could change his mind, I scaled the fence, ran onto the field, and began to play catch with him... my hero, Lefty O'Doul, asked me to shag flies for him. Joe DiMaggio, beside me in center field, yelled encouragement. ...It was almost game time. I started toward the gate, but O'Doul stopped me. "Come on," he said, and led me to the dugout. We stepped down into the dark shade of the overhang, and O'Doul said, "Hey, fellas, this is Alice...?" "Marble," I said, out of breath... ..."Let's recruit her," called the catcher, and before the afternoon was over I was the official mascot of the Seals, with the privilege of warming up with the team every time they played... During my first year in high school I grew seven inches, gained forty-five pounds, and became painfully self-conscious. At five-foot seven and 150 pounds, I was built like a fireplug; only when I was playing sports did I feel confident. I lettered in softball, basketball, and track, and I was still mascot of the Seals. My brother Dan was my idol... I suppose it was my devotion Dan was counting on when he handed me a tennis racquet. "Allie, I bought this for you. You've got to stop being such a tomboy. Go out and play tennis." I stared at him. "What will the Seals say? And the boys at school? I won't play that sissy game!" ...After school, I walked to Golden Gate Park with Mary, the only girl I knew who played tennis... Before the week was out I was hooked. Dan was delighted. |

|

1932: Eleanor "Teach" Tennant (pages 17-20) ...the state's number one player and seventh in the nation... but I knew I had gone as far as I could on my own... I decided to postpone my education and get a job so that pay for lessons with Eleanor Tennant... Before I had a chance to contact her, she came to me... I could see that my mother and Dan both liked her, but they were reluctant to say yes to the sweeping plan that she proposed--that I spend a month with her several times a year, earning my lessons by helping her with her other students and doing her secretarial work... at the posh Bishop School in La Jolla and at the Beverly Hills Hotel... [Eleanor Tennant] was born in 1895 in San Francisco to English parents. At the age of eleven she stole a tennis racquet from a house guest... ...in 1920 was ranked third in the country behind Molla Mallory and Marion Zinderstein--a very close third. |

Eleanor Tennant also took Alice to be coached by Harwood "Beese" White, who converted her to an Eastern grip and taught her proper tennis stroke technique, while Tennant concentrated on strategy and tactics.

In 1933, Marble and Tennant began spending a lot of time at William Randolph Hearst's ranch in San Simeon, where many of Tennant's celebrity students also visited. Alice made many friends in the Hollywood crowd.

Disaster struck in 1934, when Alice traveled to Paris to play with the US Wightman Cup team against a French team, as a warmup before the usual Wightman Cup matches against Britain. Alice collapsed during a match at Roland Garros, and the French doctor who treated her told her she had tuberculosis and could never play tennis again.

Alice returned to America and was checked into a sanatorium, which she left when it seemed to be making her health worse. During this time she was befriended by actress Carole Lombard, one of Tennant's students, in a series of telephone conversations.

|

1934-35: Recuperation and "Teach" Tennant's Nickname (pages 62-68) Four months after my "escape" from the sanatorium, Carole Lombard insisted that we see Dr. Commons, a Los Angeles physician. Carole and I still hadn't met, but she called me every day, and I knew she had been a great encouragement to Teach... I stood in front of the fluoroscope for a long time while Dr. Commons pulled the slide up and down, his bright eyes studying the screen. At last he said, "Alice, I can't tell for sure, but I don't believe you have tuberculosis. You had severe pleurisy and secondary anemia--I can believe that--but tuberculosis . . . lets get some X rays. | |

Carole Lombard & Alice Marble |

When the plates were developed, the doctor called me into his office... "Alice, you can play tennis again... Your lungs are scarred--it may have been tuberculosis--but I see no reason why you can't play tennis." As my blood count increased, so did the amount of tennis Dr. Commons allowed... On the days when Carole had her lesson, I played with her afterward, or we played doubles with Teach and another student. It was during one of these matches that Eleanor Tennant got the nickname she was to carry the rest of her life. It started with her habit of coaching the opposition while she was playing. Carole and I were beating Teach and her partner, but she still nagged us: "Alice, you were out of position on that shot." "Carole, watch the ball all the way to your racquet." "Yes, teacher dear," Carole called sweetly in response to each bit of advice. By the end of our match the name had been shortened to "Teach"--and had stuck. From that time on, Eleanor Tennant was "Teach" to everyone, even those who had never met the legendary coach. |

|

1936: US Nationals Final at Forest Hills (pages 85-87) Over the loudspeaker came the words: "This match will be between Miss Helen Jacobs, four times national champion and winner of the Wimbledon championship, and Miss Alice Marble of San Francisco." ...The first set was a blur. I was so nervous, I'm sure I played like a robot, but I made some of the right moves. I broke Helen's service and went to 3-1 before lapsing into a string of errors. Helen won, 6-4. I looked at the scoreboard, relieved that the score wasn't worse. I was going to be all right. Better than all right. Teach looked calm. Behind her in the stands were thirteen thousand fans, and they were cheering for me. It was because I was the underdog, but I loved their support all the same... Buoyed by the fans, I won the second set easily. Helen and I went to the locker room for our break... I won the first four games [of the third set] so quickly it surprised me. I kept Helen running with long drives deep to the baseline, cross-court chops, and drop shots. I had been avoiding her backhand, usually her strong side, but now I pressured it, too. The tactic surprised her. She didn't know what to expect from me. The crowd's sympathies were swinging back to the champion, now the underdog, at 4-0, but I was fueling my own fire. Hearing the cheers, Helen rallied to win two games; I took the next. The score stood at 5-2 when we changed courts. I wiped my face, dried my hands on the loose sawdust in the big green box, and walked to the west court. Helen stood six feet back of the baseline, bobbing lightly on her toes, composed, ready for me. What did I have to use against her? The American twist, with as much guts as I could put into it. I took a deep breath and served, feeling the muscles of my back bunch and stretch, grunting with the effort. The ball whined away from my racquet, threatening to spin out of its fuzzy skin. "Fifteen-love, Miss Marble." Helen met my next serve, and forced me into an error to tie the score. I served again. She lunged for the ball, but came up short. Thirty-fifteen. I put everything I had into a high bouncing service, and ran to the net. Helen tried a down-the-line backhand, but I cut it off for a winner. Forty-fifteen. We were at match point. I stood, bouncing the ball, reminded of a match three years earlier. I had had Betty Nuthall in the same spot, victory in my hands, and had lost. I decided to go to the net again, to go for broke. I served and sprinted forward, only to see Helen set up a high lob. I reversed and raced for the backline, legs pumping, gasping aloud with the effort. I was going to be short; it was going to drop beyond me, but in bounds. At the last moment, I turned, leaped, and smashed the ball. It bounced in Helen's backcourt, and was caught by one of the ball boys against the back wall. Was it in? I saw his grin, and, above the roar of the crowd, heard, "Game, set and match, Miss Marble. Four-six, six-three, six-two." I stood for a moment, trying to absorb what had happened. It was over. Helen was walking toward the net, smiling at me. My racquet slipped from my hand, and I ran to meet her. "Well played, Alice." |

|

About modern tennis players (pages 248-250) ...People ask me how I'd do against Martina Navratilova. She would have wiped me out, and that's not modesty. Just look at her. Not only is she stronger than I ever was, she's fitter. In my tlme, training didn't exist in any real sense. I thought I was doing great to run a little to build my wind. ...About thirty years ago, I created a composite "perfect player" for one of the tennis magazines. Attempting the same thing now sparks a flood of memories--and comparisons. Polish champion Jadwiga "JaJa" Jedrzejowska, who was killed in World War II, had a forehand like a rocket. With little else but that forehand she was twice runner-up at Wimbledon and once in the U.S. Open. Like JaJa, Steffi Graf can hit anything off the forehand; unlike JaJa, she can hit anything. On the backhand, Pauline Betz and Chris Evert have my vote. I was awed by Helen Wills Moody's backhand until I played Betz. Her one-handed swing was deceptively quick and very smooth, like Evert's two-hander. Bunny Ryan was a killer at the net--the best volleyer the game has ever known--until Navratilova came along. With both, the volley is and offensive move used with great finesse. Navratilova takes second place in drop shots to the 1937 U.S. Open champion Anita Lizana, who had the most frustrating, beautifully disguised drop shot I've ever seen. My smash was considered revolutionary in women's tennis, but Althea Gibson elevated the stroke to a new level with her combination of power and ease. Navratilova goes Gibson one step better in that her placement can be almost faultless. I'm glad I don't have to face Graf's serve. She's the first woman I've seen who could ace them all. Moody had a wicked, wide-breaking slice serve that drew you so far out of the court you really had to scramble to make the next return. Louise Brough gets credit for perfecting the American Twist that I liked so much. A difficult serve, it went out of style but now seems to be in vogue again. I only saw Suzanne Lenglen play twice, but she deserved the "Pavlova of the Courts" accolade of the sportswriters for her footwork. Perhaps all players should spend some time training for the ballet, as she did. Evonne Goolagong Cawley was the second most graceful player I've seen. Navratilova, Graf, Evert, Sabatini, Seles--all of these modern players cover the court beautifully... |

|

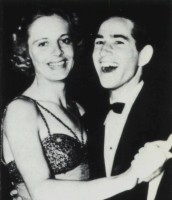

Alice Marble won the US National Singles title at Forest Hills in 1936, 1938, 1939, and 1940, the Wimbledon singles in 1939, and 13 US and Wimbledon doubles and mixed doubles titles from 1936 to 1940. At The Championships at Wimbledon in 1939, Alice Marble and Bobby Riggs both won the singles and doubles titles (Alice with Sarah Fabyan and Riggs with Elwood Cooke), and they won the mixed doubles together. The singles winners danced the first dance at the Wimbledon Ball-- a tradition abandoned decades later when the event was moved to a venue without a dance floor. That year Bobby Riggs had bet on himself to win all three titles. At a legal bookmaking shop in London, Riggs got odds of 3 to 1 against him winning singles, then 6 to 1 on doubles, and then 12 to 1 on mixed doubles. He bet £100, which paid £21,600 when he won-- the equivalent of $108,000 at the time. Alice was ranked # 1 by the USLTA from 1936 to 1940. After 1940, she turned professional, first earning $75,000 for a tour of the US, then playing exhibitions and holding clinics for soldiers during World War II. Alice married US Army Captain Joseph Crowley, then was widowed when his plane was shot down over Germany. She also relates in her book how she was recruited to do a bit of spying for Army Intelligence during the war. |

Alice Marble & Bobby Riggs 1st Dance at 1939 Wimbledon |

|

Alice remained active in her later years, attending the US Nationals (later the US Open) and Wimbledon and meeting and helping younger players. Reconciling with Teach Tennant after a falling out, she helped her old coach train Teach's new champ, Maureen "Little Mo" Connolly, for a while. Later, Alice also trained young Billie Jean Moffitt (King). Alice Marble died on December 12, 1990, at the age of 77. | |

Find more books by or about Alice Marble at Amazon.com

Find tennis shoes made by: adidas -- Nike -- Fila -- Reebok

Find tennis racquets made by: Yonex -- Wilson -- Head -- Prince -- Babolat

Find tennis balls made by: Wilson -- Dunlop -- Penn -- Tretorn -- Slazenger

Tennis pages at quickfound.net:

- Tennis History Book Excerpts:

Courting Danger by Alice Marble with Dale Leatherman

Tennis Styles and Stylists by Paul Metzler

Chrissie: My Own Story by Chris Evert with Neil Amdur

Courting Triumph by Virginia Wade with Mary Lou Mellace

The Game by Jack Kramer about Pauline Betz & Gussy Moran & more

Beyond Center Court: My Story by Tracy Austin with Christine Brennan

Evonne!: On the Move by Evonne Goolagong with Bud Collins

Court On Court: A Life in Tennis by Margaret Smith Court

Goddess & the American Girl: Suzanne Lenglen & Helen Wills by Larry Englemann

Hard Courts by John Feinstein about Mary Carillo & John McEnroe & more

Ladies of the Court by Michael Mewshaw about Mary Joe Fernandez & more

A Long Way, Baby by Grace Lichtenstein about Rosie Casals

Monica by Monica Seles & My Aces, My Faults by Nick Bollettieri Seles at Bradenton

Tough Draw by Eliot Berry about Nick Bollettieri

The Courts of Babylon by Peter Bodo: Tournament Draws

The Courts of Babylon by Peter Bodo: Dawn of the Pro Tours

- Tennis Articles

1946 TIME: Pauline Betz, Doris Hart, Beverly Baker, Gussie Moran

plus current tennis article feed

1951 & 1952 TIME: Maureen Connolly - Tennis News and Links

- WTA 2004 Desktop Wallpaper

- Justine Henin-Hardenne Desktop Wallpaper

- Maria Sharapova Desktop Wallpaper

- Anastasia Myskina Desktop Wallpaper

- Anna Kournikova News and Links

- Anna Kournikova Desktop Wallpaper

- Martina Hingis News and Links

- 2004 WTA Player Interview Videos

This page's URL is: //tennis.quickfound.net/history/alice_marble.html